What Art Is

What Art Is

What Art Is

What Art Is Anti-Art Is Not Art

by Michelle Marder Kamhi

The recent controversy provoked by the Jewish Museum's exhibition Mirroring Evil: Nazi Imagery / Recent Art is only the latest--and undoubtedly not the last--skirmish in a decades-long war between the public and the contemporary artworld. As in previous cases, the media have mistakenly attributed the conflict to the offensive content of the works. The fundamental problem, I maintain, is the anti-art tradition to which such work belongs.

In one of the disputed pieces, the purported artist inserted an image of himself, holding a Diet Coke, into a famous photograph of concentration camp inmates. In its press release, the museum claims that such work employs "the challenging language of conceptual art" to lead us "to question how images shape our perception of evil today." Outraged members of the public charge that images employing such banal references to commercial culture have the effect of trivializing the enormity of the Holocaust.

An underlying question that ought to be seriously debated, however, is the one alluded to by an elderly protester outside the Jewish Museum. He carried a sign that stated "This is not art."

For today's artworld, of course, the question "but is it art?"--so frequently raised by the public with regard to contemporary art--can never be answered in the negative. Anything made by anyone claiming to be an artist is, ipso facto, art. Anything, and anyone. That is the bottom line of what philosophers have dubbed the "institutional theory." But the ordinary person senses there is more to art than simply inserting oneself into a documentary photograph. Unlike the artworld, John and Jane Q. Public have continued to doubt the legitimacy of conceptual art--the category to which most of the "controversial art" of recent years belongs.

Conceptual art has been defined as "various forms of art in which the idea for a work is considered more important than the finished product, if any." If Michelangelo were a conceptual artist working today, he wouldn't have to labor for years to paint the Sistine ceiling, he could simply enlarge photographs of other artists' work or of scenes from biblical films and make a grand collage. Indeed, we now have a whole generation of "visual artists" who can neither paint nor sculpt.

Consider Damien Hirst--one of the controversial "young British artists" whose work was featured in the Brooklyn Museum exhibition "Sensation" two years ago. Hirst recently confided in an interview with Charlie Rose that, while he would really like to be a painter and represent the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface, he had "never really done that." As to why he hadn't done so, he frankly admitted: "I tried it and I couldn't do it." Faced with the void of a blank canvas, as he further explained: "I don't know what the hell to do."

So, like other conceptual "installation artists," Hirst has resorted to appropriating real objects and arranging them for display, rather than imaginatively re-creating reality through painted or sculptured forms. The result is controversial pieces such as his infamous dead shark preserved in a vat of formaldehyde, pretentiously entitled "The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living."

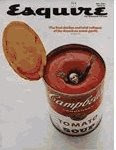

"Conceptual art" in its various guises originated in the 1960s, as a reaction against Abstract Expressionist painting, and against critics who emphasized the formal qualities of visual art without regard to its content or meaning. Like the influential "readymades" of Marcel Duchamp, it began as a rejection of the contemporary artworld. It was, essentially, an anti-art movement. One of its earliest theorists even suggested that it might be better to refer to such work by some other term than "art" and to recognize it "as an independent, new activity, irrelevant to art."[*]

Today's practitioners of conceptual art have turned their attention to social and political concerns. But their installations are based on forms and methods derived from an anti-art impulse. Such works aren't art today anymore than they were at their origin. In treating them as art, museum professionals and the press endow them with unmerited value and prestige.

Running concurrently with the Mirroring Evil show at the Jewish Museum is another on the theme of the Holocaust: An Artist's Response to Evil: "We Are Not the Last," by Zoran Music--an exhibition of paintings by a Slovenian-born painter who is a Dachau survivor. Unlike the works of conceptual art on the floor below, Music's paintings do not trivialize the event by relying on simple-minded appropriations from commercial culture to convey their meaning.

Instead Music did what real artists have always done (for background, see the museum's press release). Through a visual transformation of what he had witnessed, he created images that express something important and deeply felt about the human condition--in this case, the unspeakable horror of the Nazi death camps and the testimony they bear to the barbaric cruelty some members of the human race are capable of inflicting on their fellow men.

Museum officials report that no one has publicly objected to these images. Clearly, the medium contributes largely to the message.